Trying to Understand Entropy

This post is going to try to answer the question: “What exactly is entropy”? Mathematically, the question is answered easily enough. Suppose we have some probability distribution $p(x)$ over a state space with $m$ outcomes $\{x_1, x_2, … x_m\}$. In this post we will stick with a discrete state space since they make the intuition more clear. The entropy $H$ is defined for such a distribution as:

\[\begin{equation} H[p] = - \sum^m_{i=1} p(x_i) \log p(x_i) \end{equation}\]Where $\log$ is meant to denote the logarithm with base $e$.

Ok, but what actually is the entropy? How can we understand it? It is the cornerstone of Information theory, is a fundamental quantity in statistical physics, and appears all over the place in Machine Learning, so the task seems worthwhile.

Generally it is described as some sort of measure of uncertainty, information, or surprise associated with a random event. It is also usually described as characterizing the width of a probability distribution. While these interpretations are fair, they are a little imprecise. For instance, why do we need entropy to describe “uncertainty” in the random outcome when something like the variance can describe this perfectly well? It seems like we could come up with many ad-hoc formulae for something like uncertainty. For this reason, arguments such as these don’t really convince me of why entropy is special. Instead, I will present what I think is the most intuitively satisfying picture of entropy: the so-called “Wallis derivation”, presented in (Jaynes, 2003), pages 351-255. I will first derive the formula for entropy, and then reason through its appearance and utility in physics and information theory.

Coming up with Entropy

Suppose you have some setup for performing random experiments, and each time you run an experiment you get one of $m$ possible outcomes $\{ x_1, …, x_m \}$. This can correspond to a coin toss with $m=2$, a roll of a single die with $m=6$ or many other scenarios. We will stick with the general setup. Now consider the following problem: how do you go about assigning probabilities, $p(x_i)$ to each outcome, if you can’t actually run the experiments, and if you know nothing else about the system?

The Principle of Indifference

An intuitive solution to the problem is that if we don’t know anything at all about our experimental outcome, then we have no reason to assume one outcome, $x_i$ is any more or less likely than any other, $x_j$. Thus, the most reasonable thing to do is to be indifferent to what each outcome actually is, and assign an equal probability to everything. This rule, intuitively understood as far back as the 1600s, is called the “principle of indifference” (Keynes, 1921).

Generalizing the Principle

Let’s apply the principle in a different, slightly more general way. Say we ran the experiment $N$ times, where $N$ is large. We’d get some sequence of $N$ outcomes like $(x_{m-2}, x_1, x_1, x_3, x_m,…)$, where some outcomes will repeat. Given such a sequence, we can count the number of times outcome $x_i$ occurs, and call it $n_i$. Now, if we ran the experiment $N$ times, and we saw outcome $x_i$ occur $n_i$ times, then we can estimate the probability $p(x_i) \approx \frac{n_i}{N}$. We would expect that the larger $N$ is, the closer we’ll get to the true probability. If we had observed some other sequence of $N$ outcomes, our probability estimates will be slightly different. In this way, the observed sequence induces an assignment of probabilities.

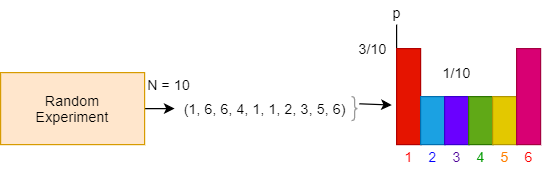

The figure below gives an example of this paradigm, in the case where our experiment consists of rolling a 6-sided die. Here, we have $m=6$ (6 outcomes) and we perform $N=10$ runs of the experiment.

Now keep in mind the crux of the problem: we can’t actually run these experiments, and we’ll need to reason about these sequences in a different way. In fact, we’ll appeal to the principle of indifference on these sequences. Since we don’t have any other information, we’ll say that all sequences are as likely to occur as each other.

What does this mean for the probability assignments? It is possible for many sequences to give us the same “outcome counts” $\{ n_1, n_2, … n_m\}$, and therefore the same assignment of probabilities. Let’s denote an assignment of probabilities by the vector $\mathbf{p} = (p(x_1), p(x_2), … p(x_m)) = (n_1/N, n_2/N, … n_m/N)$. What we are interested in is the probability distribution over the possible assignments $\mathbf{p}$, which we’ll denote $P(\mathbf{p})$. The principle of indifference tells us that each sequence is equally probable. This means that an assignment $p$ is more probable if there are more distinct sequences which give rise to the same assignment, or equivalently, the same set of outcome counts $\{n_1, n_2,… n_m\}$.

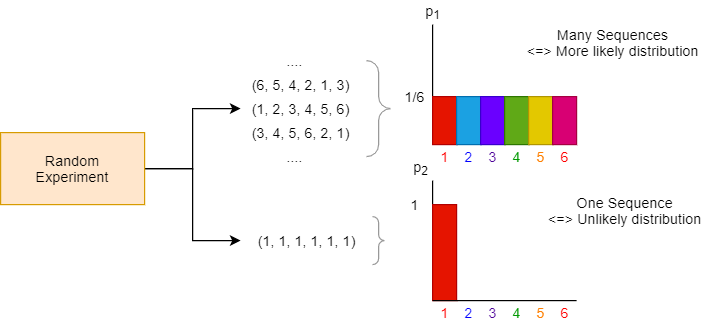

Let’s think through what this means in the case of our 6-sided die example. For convenience we’ll consider $N=6$ runs. The figure below shows 2 sets of sequences: the upper set corresponds to the uniform probability assignment $\mathbf{p_1}$ (and the outcome counts $\{n_1 = 1, …, n_6 = 1\}$), while the lower set corresponds to the probability assignment placing all mass at $x = 1$, $\mathbf{p_2}$ (and the outcome counts $\{n_1 = 6, n_2=0,.. n_6=0\}$). We can see that there are many possible distinct sequences leading to $p_1$ (there are $6!$ in fact), while there is just $1$ sequence leading to $\mathbf{p_2}$. Since these sequences are equally likely, the probability of an assignment $\mathbf{p}$ is entirely determined by the number of sequences corresponding to $\mathbf{p}$. We’d like to say that $\mathbf{p_1}$ is a much more likely (and therefore reasonable) distribution to guess, while $\mathbf{p_2}$ is very unlikely.

Let’s make these ideas more precise. In the process of calculating, we will see the entropy naturally appear. If we denote by $W(\mathbf{p})$ the number of distinct sequences which have the specified probability assignments $p$, we have:

\[\begin{align} P(\mathbf{p}) &\propto W(\mathbf{p}) \\ &= \frac{W(\mathbf{p})}{Z} \end{align}\]Where $Z$ is some normalizing factor.

To calculate $W(\mathbf{p})$, we can do some combinatorics. We are interested in the number of ways we can choose $n_1$ objects of one type, $n_2$ of another type, …, and $n_m$ of a last type, out of a total group of $N$ items. Consider a certain specific sequence which has the prescribed outcome counts. There are $N!$ possible permutations of this sequence. If $x_1$ occurs $n_1$ times, then there are $n_1!$ possible ways we can shuffle it around while giving the same sequence. Shuffling around within each outcome gives the same sequence, so the $N!$ overcounts by a factor of $n_1! n_2! n_3! … n_m!$. Correcting for this gives us $W(\mathbf{p})$:

\[\begin{align} W(\mathbf{p}) &= \frac{N!}{n_1! n_2!...n_m!} \end{align}\]Now that we have a complete description of the probability, we can ask for the most likely assignment $\mathbf{p^{*}} = \mathrm{argmax} \; P(\mathbf{p})$. We will pick this $\mathbf{p^{*}}$ as our guess for the most “reasonable” distribution.

We can see that this involves maximizing $W(\mathbf{p})$. Since $\log$ is a monotonically increasing function, we can instead maximize the quantity $\log W(\mathbf{p})$.

\[\begin{align} \log (W(\mathbf{p})) &= \log\Big( \frac{N!}{n_1! n_2!...n_m!} \Big) \\ &= \log(N!) - \sum_{i=1}^{m} \log(n_i!) \end{align}\]Next, we take $N$ large (and consequently $n_i$ large), and apply Stirling’s approximation for the factorial: $\log(n!) \approx n\log(n) - n$.

\[\begin{align} \log (W(\mathbf{p})) &\approx N\log N - N - \sum_{i=1}^{m} (n_i \log n_i - n_i) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^{m} (n_i\log N - n_i) - \sum_{i=1}^{m} (n_i \log n_i - n_i) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^{m} (n_i \log N - n_i \log n_i) \\ &= -N\sum_{i=1}^{m} \frac{n_i}{N} \log (\frac{n_i}{N}) \\ &= -N \sum_{i=1}^{m} p(x_i) \log p(x_i) \\ &= N H[ \mathbf{p} ] \end{align}\]This derivation leads us to the entropy: $H[\mathbf{p}] = \frac{1}{N} \log (W(\mathbf{p}))$. The entropy of a distribution is a quantity which reflects how likely that distribution is, under the principle of indifference.

We determine our probability $\mathbf{p}^{*}$ by maximizing the entropy (since it is equivalent to maximizing $\log W(\mathbf{p})$, under the constraint that $\mathbf{p}$ be normalized, ie. $\sum_{i=1}^m p(x_i) = 1$. We can do this by simply setting the gradient $\nabla_\mathbf{p} H = 0$, since the function $H$ is convex. Each $p(x_k)$ is then determined as:

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial}{\partial p(x_k)} H &= 0 \\ -\frac{\partial}{\partial p(x_i)} \sum_{i=1}^{m} p(x_i) \log p(x_i) &= 0 \\ -\log p(x_k) - \frac{p(x_k)}{p(x_k)} &= 0 \\ p(x_k) &= \exp(-1) \\ p(x_k) &= \mathrm{constant} \end{align}\]We get the same number for each $p(x_i)$. Next we must enforce the constraint. Since the constraint is simple (and doesn’t influence the optimization), we can do it manually. Upon normalization, we get a uniform distribution over the $m$ outcomes, so that $p(x_i) = \frac{1}{m}$.

This is exactly the same result the regular principle of indifference gives us. This makes sense, we’d have cause for concern if we got any other result!

So what was the point of doing this long calculation? Both methods allowed us to pick the most “reasonable” probability assignments when we lack information. The difference is that by phrasing the problem in terms of maximizing entropy, we can easily work with constraints.

For instance, suppose that in the above problem, we were given one extra piece of information: the mean outcome $\mathbb{E}[x] = \bar{x}$. This means that the probability assignments $\mathbf{p}$ must satisfy $\sum_{i=1}^{m} x_i p(x_i) = \bar{x}$. Now we must pick the probability assignment $\mathbf{p}$, under this constraint, which is most likely.

There isn’t a straightforward way of doing this if we were using the regular principle of indifference, but using the entropy, it is easy. We add in the constraint as a Lagrange multiplier and maximize the objective $H[\mathbf{p}] - \lambda (\bar{x} - \sum_{i=1}^{m} x_i p(x_i))$. Note that we had no need of adding a similar multiplier for the normalization constraint, since it is much simpler, though in principle we could have.

We can again solve this problem by setting the gradient to 0 with respect to $\mathbf{p}$ and $\lambda$. We get as our solution the distribution: $p(x_i) = \exp(-\lambda x_i)/Z$. This is the maximum entropy (and therefore the most likely) distribution with the given mean $\bar{x}$.

You might have noticed, but there is a pattern going on here. If we constrained both the mean and the variance (or 2nd moment), then the maximum entropy distribution will be (a discrete form of) the Gaussian! This is just yet another special property for our favourite distribution.

Why does it show up in Physics

The path that we took to derive the entropy was first discovered in statistical mechanics. The problem of interest there was the following: we have a system of many, small, interacting particles, and we can only measure the mean total energy $\bar{E}$. We are interested in writing down a probability distribution over the possible energies for each particle, $E_i$. Trying to estimate this distribution by observing the state of any particle is basically impossible, since we can’t make measurements precisely for a meaningful number of small objects.

Thus, we must come up with the most “reasonable” distribution over the set $\{E_1, E_2, … ,E_m\}$, under the constraint that the average energy be $\bar{E}$. This exactly mirrors the last example we calculated, so that we know the solution must be $p(x_i) = \exp(-\lambda E_i)/Z$. Indeed, this distribution is named the “Gibbs distribution” (as well as the “softmax distribution). The entropy of this distribution is equal (within a conversion of units) to the thermodynamic entropy, usually denoted $S$, and the parameter $\lambda$ is called the inverse temperature, equal to (again within a conversion of units) the reciprocal of the thermodynamic temperature.

We obtained this distribution because we thought it was the most likely, but this guess works out empirically. For instance, this distribution, combined with other definitions of physics, such as pressure and volume, is enough derive the ideal gas law, which we experimentally know to be true.

Why does it show up in Information theory

Information theory is concerned with efficient communication. Suppose we wish to send a message, which we’ll model as the output of some random source. The source outputs some character from the alphabet $\{ x_1, x_2,.. x_m \}$ at random, with probability $p(x_i)$.

For this problem, Claude Shannon made the key observation that, as far as efficiency is concerned, communication is related to choosing between a set of possible messages, rather than the content of those messages (Shannon, 1948). If our source generates messages of $N$ characters, then to “communicate a message” means specifying one out of all possible messages. If $N$ is large then every possible message must respect the probability distribution of the source. How many such messages are there? We already made this calculation in a section above: there are $W(\mathbf{p})$ such messages.

To communicate these messages, we simply label each one with an index $i$, and send the associated number. We assume that at the other end, the receiver knows which message corresponds to which index. If we represent each index $i$ as a binary number, how many bits will we need to send? Each possible message must get a unique index, so that the index number must cover $W(\mathbf{p})$ possibilities. A binary number requires $\log_2 W(\mathbf{p})$ bits to represent $W(\mathbf{p})$ possibilities.

Thus, communicating one message of length $N$ requires $\log_2 W(\mathbf{p})$ bits. The average number of bits we must send per character, $L$, is:

\[\begin{align} L &= \frac{1}{N} \log_2 W(\mathbf{p}) \\ &= \frac{1}{\log 2} \frac{1}{N} \log W(\mathbf{p}) \\ &= \frac{1}{\log 2} H[\mathbf{p}] \\ &= H_2 [\mathbf{p}] \end{align}\]Where again, we see that the entropy naturally arises. By convention we absorb the extra factor of $\frac{1}{\log 2}$ into the entropy and call the result “the entropy in bits”, treating it as a unit conversion.

Thus, this encoding scheme lets us send the message in $H_2[\mathbf{p}]$. Can we get away with using less bits? Well, that would require some possible messages to share the same index. This would mean that, for those messages, the receiver wouldn’t be able to recover the exact message we meant to send. Therefore, we cannot reduce the number of bits (without introducing some loss of meaning). In this sense, the entropy is a fundamental limit representing the “amount of information” in a source. At most, we can encode a message up to its entropy.

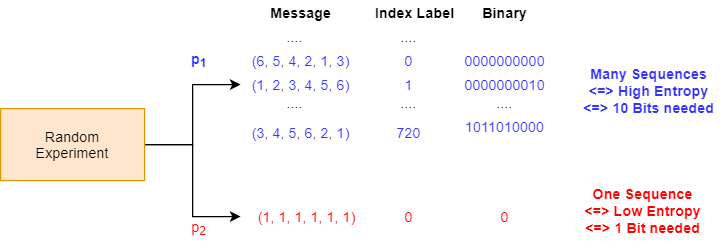

Consider our running example of a 6-sided die. We wish to send to a receiver the results of our die rolls: these are our messages. The figure below gives us examples of encoding these messages from a uniform $\mathbf{p_1}$ and a degenerate $\mathbf{p_2}$ distribution, with $N=6$. We can see that $\mathbf{p_1}$ needs many more bits (10 bits) to distinguish between all its possible messages, while the $\mathbf{p_2}$ needs 1 bit. This is reflected in their corresponding entropies. In fact, as its entropy suggests, we can even get away with $0$ bits for $\mathbf{p_2}$. How? Well, if $\mathbf{p_2}$ only produces 1 possible message (the die only ever rolls a $1$), then there is no need to transmit its outcomes at all! If we were forced to transmit something for $\mathbf{p_2}$, it would take 1 bit.

Conclusion

I hope that this post shed some light regarding entropy, and its appearance in many fields. The key takeaway from this is that entropy is a very natural consequence that comes out of reasoning about how “likely” a set of probability distributions are. Given how general its derivation is, it shouldn’t be so surprising that entropy pops up all over the place. Given its interpretation as the “likelihood of a distribution”, it also intuitively makes sense why we often maximize it in various inference problems.

Further Reading

If you are interested in this topic, I recommend checking out the links below (in addiiton to the references):

- “Principle of Maximum Entropy” Wikipedia Page - the idea of maximizing entropy as giving us a reasonable probability distribution under uncertainty can be expanded to a general principle for inference (either used alongside, or replacing Bayesian inference).

- “Jaynes’ MaxEnt Paper” - Jaynes was a big proponent of the Principle of Maximum Entropy, and this paper discusses its use as a framework for inference.

- “Leonard Susskind’s Lectures on Statistical Mechanics” - if you are interested in how probabilistic concepts show up in physics, I recommend these legendary lectures by Prof. Susskind. He starts out with basic notions of probability as a starting point for deriving the laws of thermodynamics.

- “Central Limit Theorem and Maximum Entropy” - I mentioned that the Gaussian is the maximum entropy distribution for a given mean and variance. It is also the distribution sums of i.i.d variables converge to in the Central Limit Theorem. Indeed there are some nice ways of explaining this using the idea that adding a random variable “increases” the entropy, until we converge. See the linked MathOverflow post for a discussion.

References

Jaynes, Edwin T. 2003. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science. Cambridge university press.

Keynes, John Maynard (1921). “Chapter IV. The Principle of Indifference”. A Treatise on Probability. 4. Macmillan and Co. pp. 41–64.

Shannon, C. E., A Mathematical Theory of Communication Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1948.